Land Claim Business

Native Land Claims have become big business for native bands and for the law firms that represent them. Ontario has created the Ministry of Indigenous Affairs (formerly Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation ) to deal with these “claims” and government staff is apparently instructed to settle these claims rather than go to court. Native Bands often receive tens of thousands of dollars or more up front to retain lawyers to negotiate a settlement and settlements generally involve millions of dollars as well as more land. When virtually every treaty from the 1800's becomes open to interpretation and subject to "renegotiation" one has to ask whether these are really valid claims or just another way for the government to give more money to the natives.

Public Has No Representation

The government’s position is that the public is not a party to these “negotiations” and therefore has no standing in deciding whether a claim is in fact valid. MIA claims to hold information sessions but these occur after a tentative decision has been made and are used to promote the proposed negotiated deal. Local residences who may have pertinent relevant information are denied an opportunity to present their facts in a court of law.

Wikwemikong Filed Three Claims

The Wikwemikong Band on Manitoulin Island is a good example of the Land Claim Business. Wikwemikong merged with Point Grondine Reserve in 1968 and subsequently assumed control of Point Grondine which was set aside as a Reserve under the Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850. The Robinson Huron treaty ceded all of the islands in Georgian Bay to the Crown.

Wikwemikong launched their first land claim for a larger Point Grondine which was settled and in 1997 Wikwemikong received $13,300,000 plus $600,000 in legal fees (without going to court) and a much larger Point Grondine reserve in a Settlement Agreement for all outstanding issues. The original descendants of Point Grondine were excluded from the negotiations as were nearby owners of private lands and islands.

In the same month in 1997, the same Wikwemikong Band filed a second Statement of Claim against Ontario and the Federal government for 41 fishing islands near Manitoulin Island where their Reserve is located.

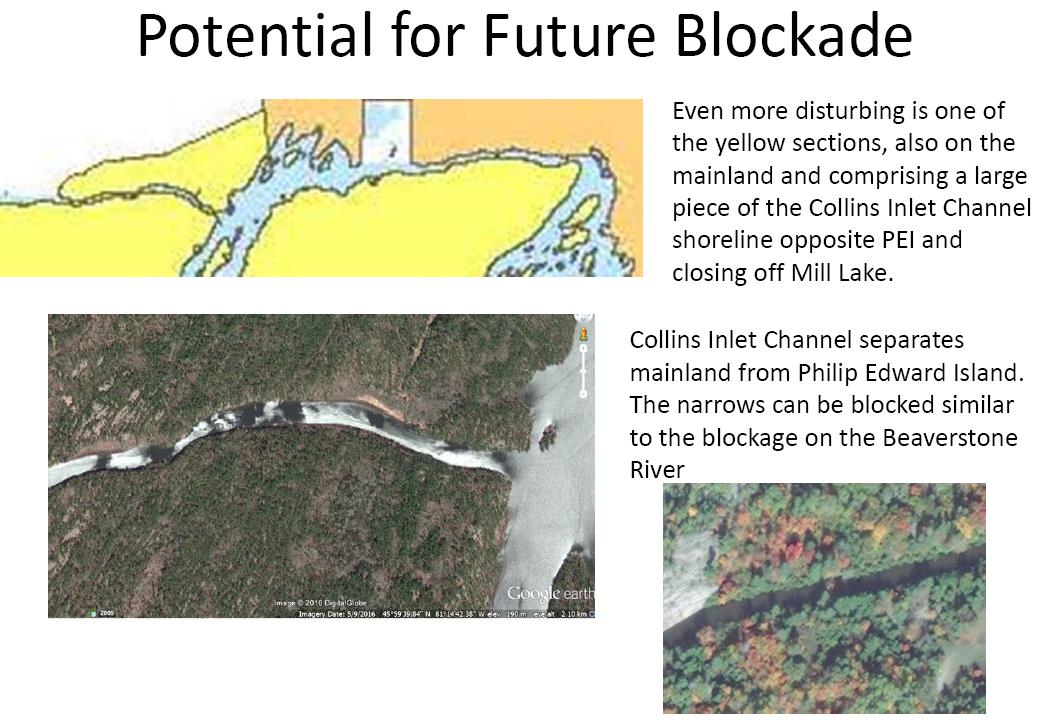

This second land claim has expanded to include thousands of islands and mainland which will also expand Point Grondine Reserve, the same Reserve which was expanded as a result of Wikwemikong’s first land claim and settlement in 1997. The proposed new expansion will encompass strategic parcels of land to give Wikwemikong control of water access into Mill Lake and Beaverstone Bay where dozens of private properties are located.

Ministry of Indigenous Affairs (MIA) only informed the nearby residents in August 2015 (18 years later) of this the second land claim by Wikwemikong being accepted and that an “alternate claim” for Philip Edward Island is now the preferred choice for settling the claim. MIA gave residents only 60 days within which to respond which eventually was extended to Jan 2016. MIA is presenting the “alternate claim” as a done deal and does not appear to be interested in the facts and that Wikwemikong has not used these “alternate” islands whereas thousands of Ontarians have and continue to use them. MIA's response was to change its name to Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation (MIRR). Wikwemikong also changed its name to Wiikwemkoong.

The Federal government

decided to not continue negotiating with Wikwemikong. Ontario is proceeding on

its own which would indicate that this is a political decision. MIRR has also decided

that it would be less expensive to give away crown owned islands rather than

negotiate a purchase of Fitzwilliam or offer Wikwemikong equivalent cash,

assuming that the claim is actually valid.

Six other native bands have also filed a lawsuit claiming the same islands as Wikwemikong. Ontario MIRR appears to be ignoring this other claim and continues to negotiate with Wikwemikong. MIRR will not explain their reasons for doing so citing confidentiality.

The original Treaty of 1836 stated that no indigenous peoples have exclusive possession of any of the fishing islands, yet Wikwemikong and Ontario are ignoring his fact.

MIRR released a draft Environmental Assessment Study Report in June 2017 that recommends the giveaway. The public had until September 15, 2017 to comment on the report and alternatives for dealing with the giveaway of thousands of islands and parts of the mainland. Two years later the Final Environmental Assessment Report was issued and it ignored the issues raised in response to the draft report. MIA did add a disclaimer absolving themselves of any responsibly or liability for any errors or omissions.

The government ESR report has been reviewed by residents of the Beaverstone Bay / Mill Lake Association (BBMLA) and their report REVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT WIIKWEMKOONG ISLANDS BOUNDARY CLAIM has been submitted to Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation (now called Ministry of Indigenous Affairs or MIA)

The government Environmental Assessment Report is deficient and BBMLA recommends that Ontario not proceed with the land transfer and requests that either Alternate 1 or Alternate 2 be implemented as the only logical courses of action to follow.

Alternative 1: Ontario does not pursue a negotiated settlement of the Wiikwemkoong Islands Claim.

Alternative 2: Re-Negotiate Proposed Settlement Lands.

Third Claim by Wikwemikong

Chief Peltier of Wikwemikong is one of the Plaintiffs in a third lawsuit claiming higher annuities under the Robinson Huron Treaty. The Statement of Claim states that he is a member of Wikwemikong Reserve No. 26 (Point Grondine) and a beneficiary under the Robinson Huron Treaty. Justice P. C. Hennessy of Ontario Superior Court of Justice agreed with the Plaintiffs in her Dec 2018 ruling.

Significance of this ruling is that Wikwemikong Chief Peltier is subject to the Robinson Huron Treaty and all beneficiaries of Robinson Huron Treaty had to cede all the islands in Georgian Bay. To receive the Robinson Huron Treaty annuities, the chief and his members must be subject to all the terms of that Treaty which included the ceding of all the islands in Georgian Bay. Chief Peltier and others on Wikwemikong cannot remove themselves from this fact and therefore, cannot claim the same islands that are subject to the negotiations for the 41 fishing islands, shown as Wikwemikong’s 2nd land claim.

These multiple claims must be put into perspective with each other and not treated as isolated claims. Point Grondine amalgamated with Wikwemikong in 1968 and the amalgamated reserve is subject to the Robinson Huron Treaty as confirmed by the recent court decision.

Evidence is Ignored

The Point Grondine Report of Nov 1993 provided affected property owners with an update during the first land claim. Wikwemikong and the Ontario government clearly stated that the 41 “fishing islands” do not include any of the islands immediately adjacent to the south shore of Philip Edward Island or any of the islands in Collins Inlet/Beaverstone Bay. Wikwemikong and the Ontario government have now reneged on this statement which questions the validity of the Point Grondine Settlement Agreement as other key evidence was also ignored in reaching that settlement.

MIA is ignoring the main issues and evidence including the use of these islands by the public which predates the arrival of the Wikwemikong band to Ontario.

MIA also ignores the Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850 which ceded all the islands and of which Wikwemikong is a signatory through its amalgamation of the Point Grondine Reserve.

Fourth Claim by Wikwemikong

This current claim will not be the last claim by Wikwemikong as this Native Band has stated that once the current island claim is concluded, they will proceed with another claim, their fourth claim for 23,000 crown owned islands covering all of the northern and most of the eastern shorelines of Georgian Bay. Most island properties in Georgian Bay will likely be impacted by this third claim should it be allowed to proceed and most likely will face similar reductions in property values as is occurring in the Killarney area of Georgian Bay.

Georgian Bay will become an Indian “Nation” with the inevitable confrontations between the non native general public and the natives.

Who are the Wikwemikong?

According to the Ontario Government in their Statement of Defense: “Some predecessors of some members of the plaintiff migrated to Manitoulin Island in the 1830s and occupied a small part of it. No predecessor of any member of the plaintiff occupied Manitoulin or any part of it between 1680 and the 1830s or, in the alternative, no predecessor of any member of the plaintiff occupied Manitoulin or any part of it at any time whatever prior to the 1830s.”

Wikwemikong members were thus considered as recent immigrants to Canada from USA at the time when the treaty of 1836 was signed and now these American Indian descendants want to own 23,000 crown islands in Georgian Bay even though they never inhabited or used these islands. When Canada fought the USA in the war of 1812, the Wikwemikong were American Indians and not Canadian.

Native Lands not accessible by non-natives

Native lands are for natives and not for non-natives. Should Philip Edward Island and the thousands of other crown owned islands be handed over to Wikwemikong, will the public be allowed to access these islands? Wikwemikong has already shown us what to expect. Wikwemikong settled its first land claim in 1995 and immediately restricted access to its Point Grondine Reserve and to the Beaverstone River which flows through the Reserve.

The Beaverstone River is a public waterway and any restriction of its use by the public contravenes the Settlement Agreement which Wikwemikong signed in 1995 and it is in violation of the Navigable Waters Act Canada’s Navigation Protection Act which states:

The public right of navigation—the right to use navigable waters as a highway—continues to be protected in Canada by Common Law, whether the waterway is listed on the schedule to the Act or not.